Story written and researched by Ed Kornhauser, 2022

Flying machines, stock fraud, a double murder, and bad weather? This little piece of San Diego history has all that, and it all happened a few blocks away from my place in Golden Hill.

Shortly after the turn of the last century the world was rife with aerial innovation. The Wright Brothers flew at Kitty Hawk in 1903. Many varied and experimental aircraft were to come, and in tandem with them came the prospect of lighter-than-air travel. Epitomized by Germany’s hydrogen-filled Zeppelins, these machines offered the prospect of passenger air travel on a grand scale.

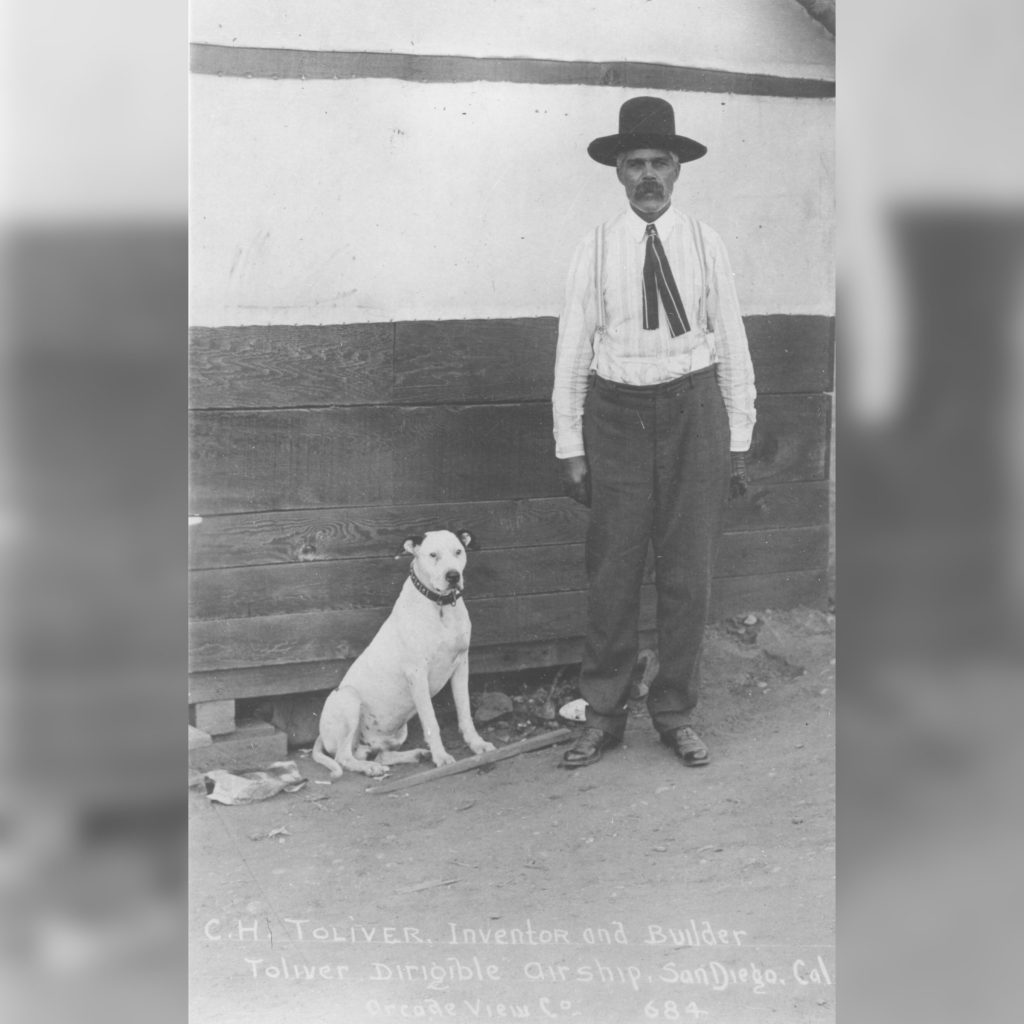

Enter Charles H. Toliver. A 49-year-old inventor and “tinkerer,” Toliver turned up in Livermore, CA in 1903 and announced his intention to build an airship. He secured land on the promise to build a well and took on investors to the tune of some $30,000 (roughly $950k today). By 1904 he had constructed a craft some 250 feet long, 44 feet high, and 40 feet wide, complete with engines he had specially designed. It’s maiden flight was set for the fall, which came and went. As did 1905, 1906, and 1907. Toliver claimed technical difficulties had set his project back. He was then sued by the owner of the land his craft was on for failing to build the aforementioned well.

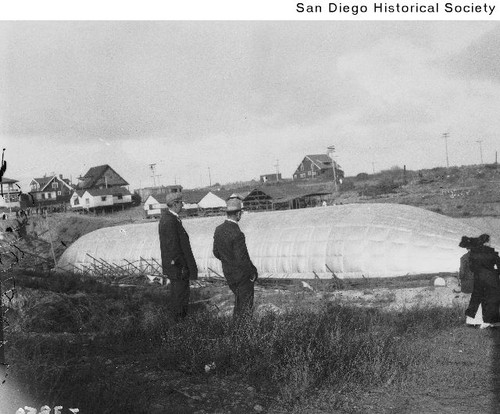

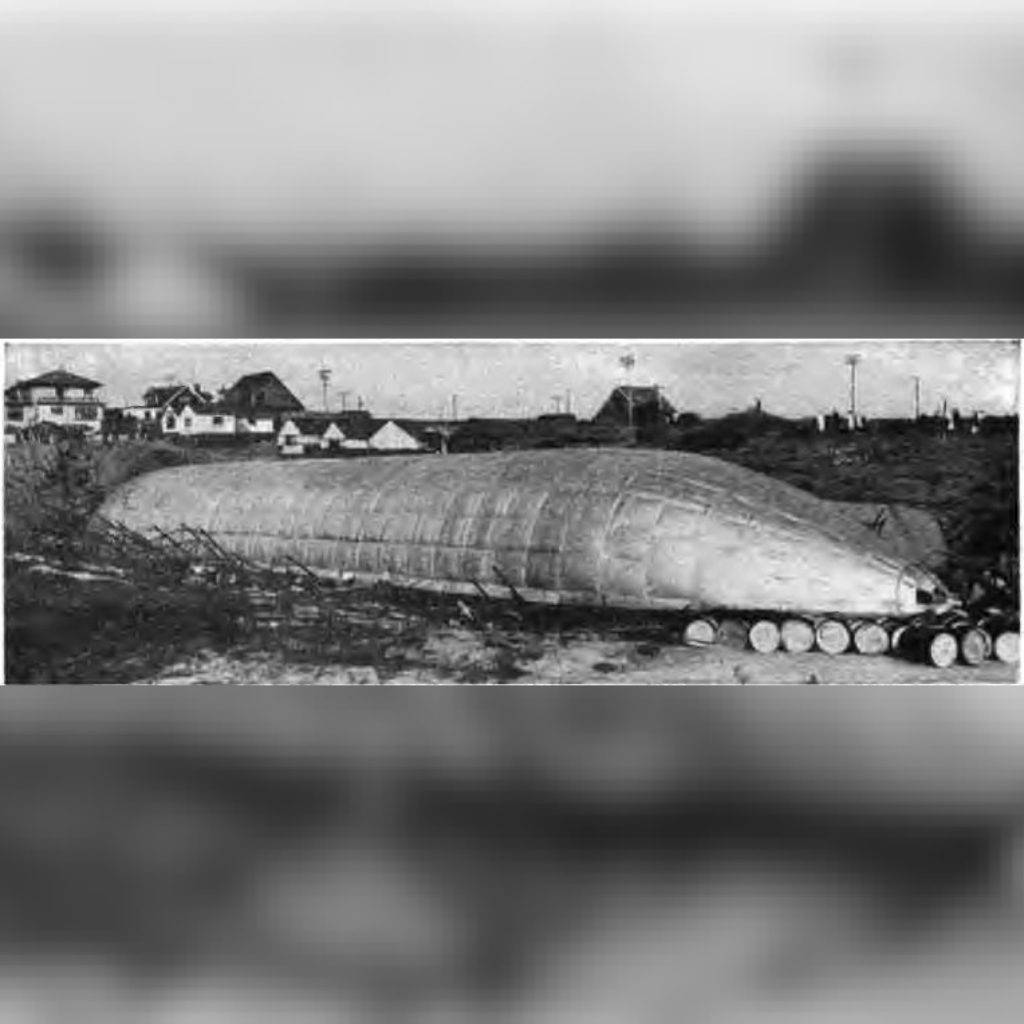

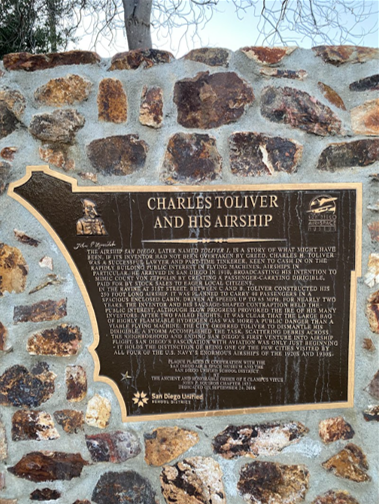

In 1910, now 56, Toliver skipped town and made his way to San Diego. Repeating his former plan, he set himself up in a ravine between B and C Streets near 31st in Golden Hill. Construction began. This new airship, dubbed the “San Diego,” would allegedly ferry passengers to Los Angeles and back at speeds of 65 mph, all whilst seated safely in a compartment built within the gas-filled envelope. He once again took investors, at $2.50 per share (about $80 today). The public ate it up. Around 3000 people turned up to the “shipyard” in 1911 to view Toliver’s creation, which he announced was 90% complete. What’s more, he claimed, shares in his company were in such high demand that they would double in price to $5 a share.

Mirroring his prior foray in airship-building, “construction issues” and Toliver’s failed promises continued into the fall. On November 10th, the newly re-christened “Toliver 1” attempted it’s maiden flight. The engines kicked on, the propellers spun, but according to The Union (predecessor to the modern Union-Tribune), “It quivered for a few breathless moments, threatening to rise, then settled down again.” Toliver blamed San Diego’s bad weather.

Soon more problems were to follow. Investors were upset that their shares were basically worthless, especially with no end in sight for the completion of Toliver’s airship. There were also allegations (complete with a lawsuit) of less-than-honest bookkeeping on the part of Toliver. However, the worst setback of all came from the city Health Department. Their concern was the presence of large amounts of hydrogen that were used to inflate (and ideally lift) the craft were hazardous to the community. Toliver was thus commanded to “abate the nuisance,” and deflate his airship “forthwith.” Toliver, in the most severe of binds, referred to his grounded airship as a “beached whale.”

Hydrogen is the lightest element on Earth, ideal for lighter-than-air travel. It’s also plentiful and inexpensive. So what’s the issue? It’s also highly flammable. The presence of so much hydrogen next to all that machinery is a fatal juxtaposition. The Hidenburg disaster in 1937, which killed 36 people, effectively ended hydrogen’s use in airships.

As it happened, the “bad weather” that Toliver had earlier blamed became manifest. On December 10th, 1911 a winter storm blew through and violently rended the Toliver 1, sending parts of it all over the area. Traffic was blocked, and the remnants were hauled to the dump. Toliver took it badly. In a contemporary newspaper, he was reported as saying, “The treatment that has been accorded me in San Diego has been unjust and cruel. This may not be the end of the destruction of that airship. Certainly the city officials have been responsible for it and certainly there should be some redress.”

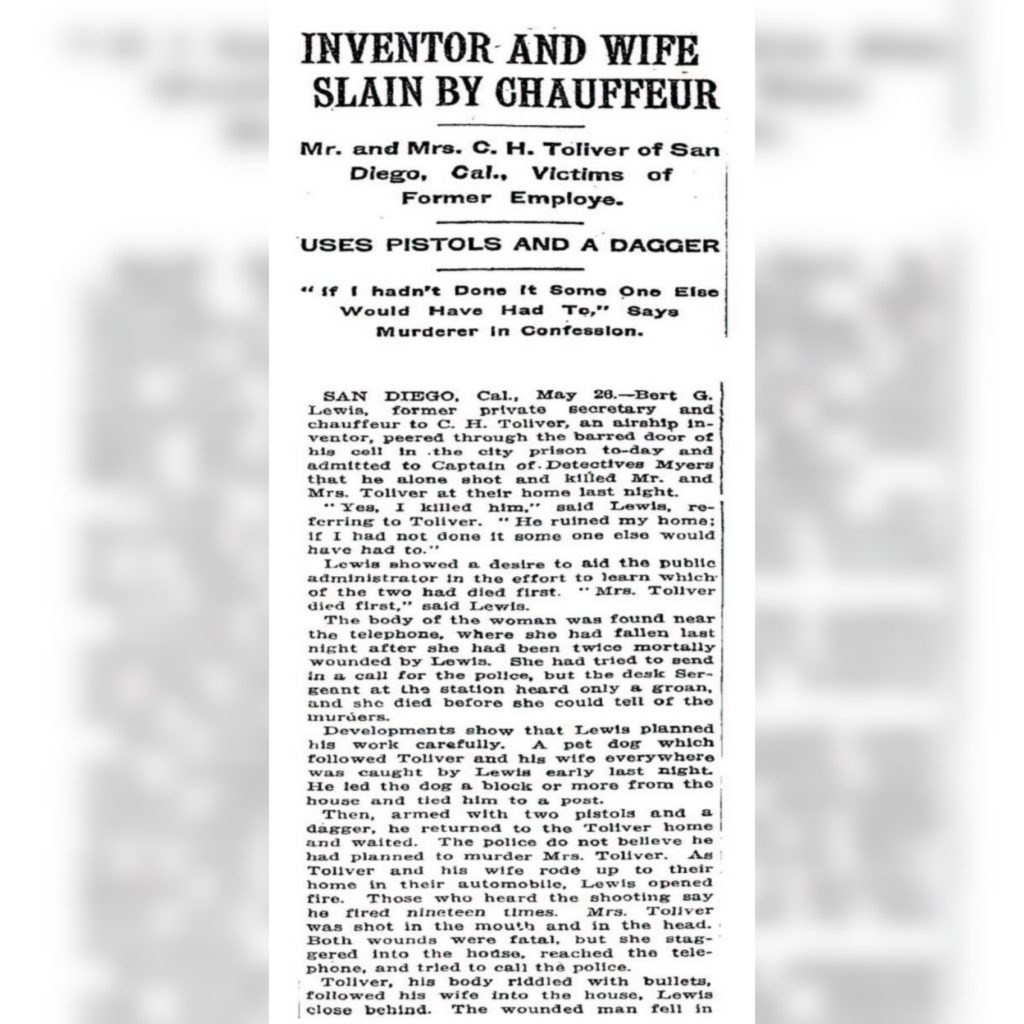

However, Toliver’s fury would not last long. He had made enemies. One such enemy was Herbert G. Lewis. Lewis was not only a shareholder in Toliver’s company, but also served as a secretary and chauffeur to Toliver himself. Furthermore, Toliver had allegedly also either had an affair with or forced himself upon on Lewis’ young Swedish wife, Ellen. Enraged, Lewis set out upon learning this. He found the Toliver house empty. He took the Toliver’s dog, tying it to a post several blocks away so as not to alert suspicion. He then lay in wait in the garage, armed with two pistols and a knife. When Toliver and his wife Kate drove home, Lewis emerged and shot them both. Kate made it inside and to the phone, managing to dial the authorities before succumbing to her wounds. Toliver also made it inside, where Lewis finished him off with his knife.

Lewis was arrested, standing trial in 1913. “I guess you’ve got the man you want,” Lewis admitted. “He ruined my home; if I had not done it some one else would have had to.” Perhaps surprisingly, Lewis was found “not guilty by reason of insanity.” Another subsequent trial found him “sane,” and he was subsequently released. One report states he and his wife relocated to Los Angeles and lived in obscurity. Another was that Ellen divorced Lewis, after which Lewis joined the circus.

I enjoy knowing the history behind the city I live in, from the things that make this place the vibrant multicultural metropolis that is, to the obscure and fascinating tales that have all too often faded into obscurity. If you’ve read this far, what’s your favorite piece of San Diego history?

Sources for this story were an online expert from Richard A. Crawford’s “An Airship or a Lead Ballon?” as well as an article on the “Toliver Airship” from the Historical Marker Database (hmdb.org)